|

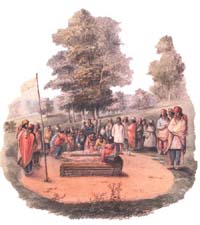

Indian burial at Kee-waw-nay, a Potawatomi village, 1837. (watercolor by George Winter, 1863-1871) enlarge |

When their husbands die, they weep in a way that would make you think they are sincerely grieved. . . . The relatives . . . come to "clothe" them, bringing them blankets, pelts, kettles, guns, hatchets, porcelain collars, belts, and knives. (Pierre Delliette, 1702)![]()

Death was a time of sorrow and mourning, especially among the close relatives of the person who died. At the death of a woman's husband, the widow sang a funeral song lamenting not only her personal loss but also the potential hardships facing her and her children. To express their esteem for the deceased man and their pity for the widow, relatives presented gifts to the mourners, including such objects as blankets, animal pelts, kettles, and guns. The mourners were expected to express gratitude to their relatives by giving gifts in exchange, although these items could be of lesser value than the ones they originally received.

They . . . pay four men for burying the dead. . . . [T]hey paint his face and hair red, put a white shirt on him if they have one, some new leggings of cloth or of leather, and moccasins, and cover him with the best robe they have. They put in a little kettle or earthen pot, about a double handful of corn, a calumet, a pinch of tobacco, [and] a bow and arrows. (Pierre Delliette, 1702)![]()

The Illinois practiced two different burial programs: the burial of intact bodies (primary interment) and the burial of disarticulated skeletons that had been placed on scaffolds before burial (secondary interment). Except in the case of young children, burial crews were of the same age and sex as the deceased (men buried men, girls buried girls, and so on). In the case of a primary interment, the crew dug a grave and lined it with wooden boards. Then they dressed the body and placed it in the grave with funerary objects meant to accompany the spirit of the deceased into the afterlife. Finally, they erected a wooden cover over the grave to prevent animals from entering the burial chamber.

After this, so the old men say, they think of procuring for [the deceased] passage over a great river, on whose nearer shore they hear delightful things. There, they say, there is continual dancing, they have everything they wish to eat, the women are always beautiful, and it is never cold. (Pierre Delliette, 1702)![]()

The Illinois believed in life after death. On its journey to the afterlife, the soul of a person traveled to a blissful place that lay beyond a great river. To ensure that the soul was able to complete this journey, relatives of the deceased arranged a funeral ceremony. The ceremony, called the "discovery dance," was performed by a shaman, a drummer, and warriors representing all of the relatives' villages. At the conclusion of the dance, the relatives organized recreational activities that the deceased had enjoyed in life, such as lacrosse, footraces, or games of chance.![]()

|

|

Copyright © 2000 Illinois State Museum